How a Bavarian wedding celebration became one of the province’s most beloved fall traditions

To understand how Ontarians began celebrating fall with beer, lederhosen and Bavarian cuisine, you have to go back to 1810, when Prince Regent Ludwig of Bavaria (who would eventually become King Ludwig I) and Princess Therese of Saxony-Hildburghausen celebrated their marriage with a five-day carnival in Munich. It was such a hit with the city’s populace – who doesn’t love nearly a week of revelry? – that the next year, they did it again, combining it with the state fair. By 1818, it was an annual event, with booths selling the region’s signature beer and sausages. Oktoberfest, Germany’s famous two-week celebration of the fall harvest, was born.

Fast-forward to southern Ontario in the late 1960s, when a German club in a city once called Berlin (which was subsequently renamed Kitchener during the First World War during a wave of xenophobia) decided to throw its own Oktoberfest to mark Canada’s 100th birthday. That first celebration at the Concordia Club in 1967 drew around 2,500 people, so the next year they invited a few other German clubs in the area to join in, almost doubling the crowd.

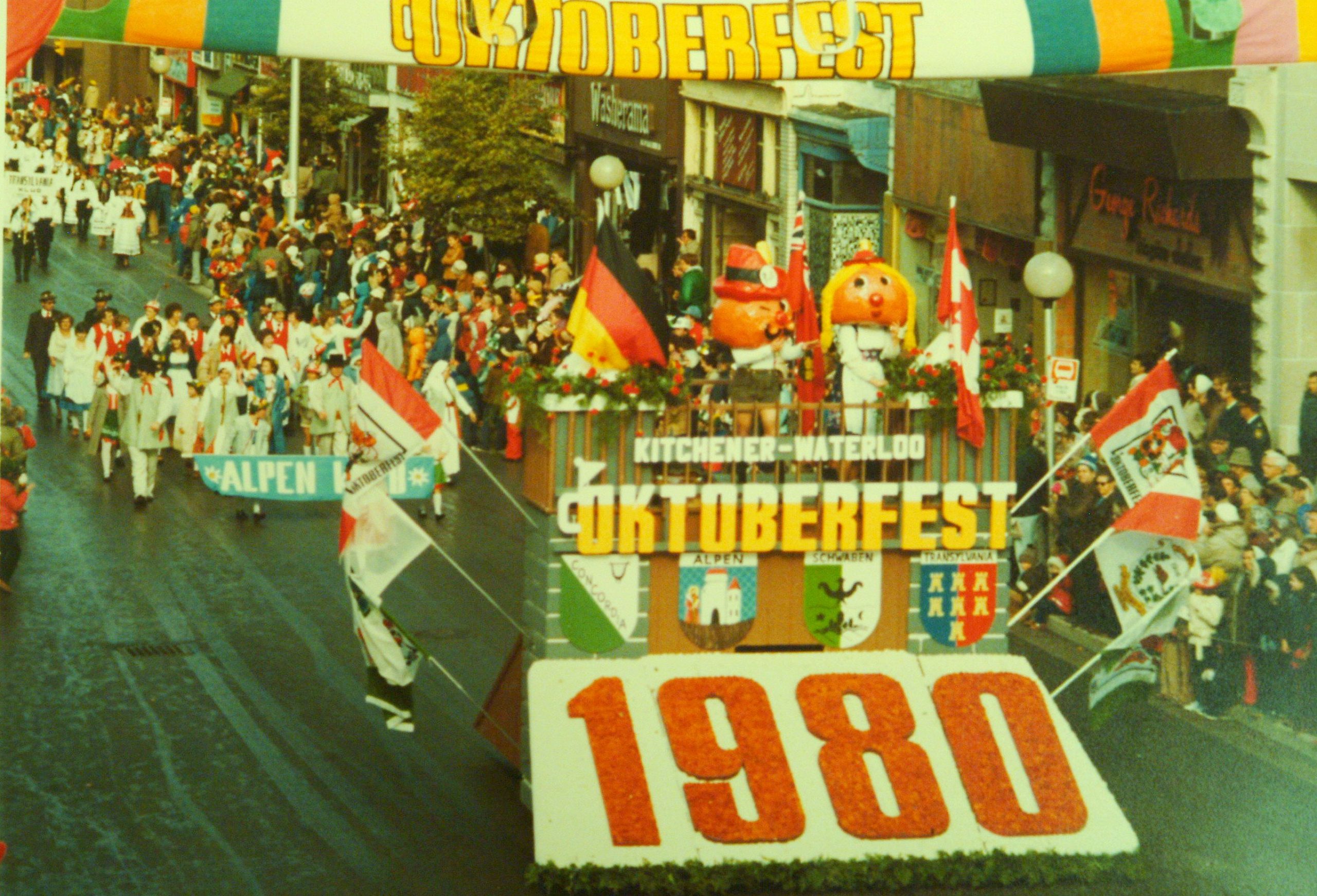

By 1969, the area’s chamber of commerce spotted a promising tourism opportunity, and the event became known as Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest, Ontario’s first and longest-running ‘volksfest,’ the German term for an outdoor event that combines a beer or wine festival with a fun fair. In the first year alone, it attracted 75,000 people, who ate and drank their way through 57,000 gallons of specially-brewed Bavarian beer and 50,000 pounds of sausages. (Not bad for an event that started with a $200 budget!)

And while the crowds are a bit bigger now – more than 700,000 people attended at the pre-pandemic peak – the festival really isn’t so different from the grainy Kodachrome snaps of those early years, where smiling faces cheers the camera, stein of beer in hand, or laughing children twirl each other around a dance floor, the skirts of their traditional dirndls spinning around them, a polka band playing in the background.

The spirit of the festival is certainly unchanged, says Allan Cayenne, the festival’s president. “We call it ‘Gemütlichkeit,’ which is a welcoming atmosphere,” he says, referring to a word that doesn’t quite translate into English, but implies a cross between warmth and good cheer and means something akin to coziness.

How that plays out across the festival, however, is very much a choose-your-own Bavarian adventure. “Everyone has their own thing about the festival that makes it special for them,” says Cayenne, who is not German himself but grew up in the Kitchener area and fell in love with the festival’s open-hearted, open-armed joy – not to mention its impact on the community through charitable giving. “Some people book a table for dinner and then they’ll move into grabbing some drinks and playing some games,” he says. “Other people go straight to the bar and enjoy a beer, while other people will head straight to the dance floor.” The annual Thanksgiving Day Parade, which draws thousands, is also a festival highlight. “Everyone can come and be German for the day,” says Cayenne of the festival that’s running in Kitchener-Waterloo this year from Sept. 23 to Oct. 15.

Key to many Oktoberfest are its “festhallen,” which literally translates to “festival halls,” but can really be anywhere the tradition is celebrated. At the Kitchener-Waterloo event, along with a centralized “Willkommen Platz”– a literal “welcoming place” in the city center with performers, food vendors, and two beer tents – they have a variety of festhallen across the region, including those hosted by the area’s different German clubs, each with its own flavour, literally.

“Each of the German clubs were founded by people who trace their roots to different parts of Bavaria or German-speaking Europe,” explains Cayenne. “They each have their own atmosphere and unique food offerings.” The Alpine Club, for example, is the place to go for home-made strudel (get there early, because it tends to sell out!), while the Transylvania Club is known for the traditional delicacy pig tails, the Schwaben Club is the cabbage roll destination, and Hubertus Haus offers rollbraten, a pork roast you might not find anywhere else. “Concordia Club makes a mean schnitzel,” adds Cayenne, who’s been in the kitchens with many of the clubs as they’ve made their specialties.

“You get a different experience depending on where you go,” he says. “That’s awesome, because sometimes people are looking for that big tent set up, similar to what you’d see in Munich, where you’ve got two or three thousand people to celebrate with. Sometimes you just want that cozy atmosphere with 200 people where it’s a little more intimate.”

That intimacy and sense of connection is something that Justina Klein, one of the co-founders of the Toronto Oktoberfest, loves about the celebration. “It’s such a friendly festival, because it’s about camaraderie,” she says. “A 70-year-old can sit down next to a 20-year-old, and they become best friends by the end. Everyone’s talking to each other, and everyone just wants to have fun.”

Klein and her partners started their event in 2012, inspired by a visit to the Kitchener-Waterloo festival. “I was shocked that Toronto didn’t have its own,” she says. “Oktoberfest is one of the biggest fall festivals around the world. How could we not be celebrating this?” Their first event, held in a hall across from St. Lawrence Market, drew 800 people. Ten years later, they see around 8,000 people over two days at Ontario Place.

As part of the team who launched the Toronto Christmas Market, Klein had spent lots of time in Germany, and was determined to make this Oktoberfest as authentic as possible.

“We brought in the real Bavarian tables,” says Klein, referring to the long, thin wooden style with bench seating. They also use authentic glass beer steins, which as Klein says, “is not without risk, but people love it.” Their beer, unlike other festivals, which may do a mix of local and international, is only from German or European brands. In fact, this is one of the few places where you can get your hands on German brewery Erdinger’s annual Oktoberfest brew, which is flown in specially for the festival. They go through 25,000 pints of beer each year, washing down 10,000 schnitzels and sausages.

“It’s so important that people walk into that festival hall and they’re transported,” says Klein, who uses Bavarian fabric swags, garlands and wreaths to decorate the ceilings. “We’ve had people who’ve been to Munich tell us they can’t tell the difference,” she adds with pride.

The entertainment which started off with George Kash, an Oktoberfest legend who’s been entertaining crowds with “oompah” music for over 50 years, has also grown to be an important part of the Toronto Oktoberfest. “We’ve created our own vibe,” says Klein. Think a cabaret-style show that features a Bavarian burlesque singer, and a dance competition called “So You Think Can Tanze,” where traditional Bavarian dancers teach amateurs some moves, and the audience votes. “We try to mix the old with the new,” says Klein, of the festival that will be taking place at Ontario Place on Sept. 30 and Oct. 1 this year.

Over in Vankleek Hill, near the Quebec border, all eyes are on the stage as well. Specifically, the moment of the first keg “tapping,” when a ceremonial beer is poured to kick off Oktoberfest at Beau’s Brewery, followed by the singing of the German and Canadian national anthems, plus a land acknowledgement.

“It’s the only time that I’m up on stage throughout the festival, and I’m looking out at a sea of little green hats, and the biggest smiles you ever saw,” says Jennifer Beauchesne, senior brand manager at Beau’s All Natural Brewing Co., a craft brewery in the town. “It’s just that moment when you know that you’ve created something magical for people and you see the impact of bringing people together.”

Beauchesne will be the first to tell you that Beau’s Oktoberfest started as a marketing stunt to launch a new seasonal beer. “We knew we were in love with nice, clean German beers, and we had this one coming out that was specifically an Oktoberfest beer, so we thought, why not?”

In nine weeks, they pulled together a festival, serendipitously booking George Wendt, aka Norm from Cheers, which got them some press. “We sold 5,000 tickets,” she recalls of the surprising reception. “We thought a couple hundred people would come out and stand in a field and drink beer with us, so it blew us away.”

In time, the festival eclipsed those modest beginnings. Always designed as an Oktoberfest for “a high-level lover of beer,” Beau’s added an educational component, including seminars about food and beer pairings, for example. They began to bring in beers from other breweries, debuting around a dozen new beers every year. They pioneered a “Stein hold struggle” – like tug-of-war but with a beer glass – and a sausage eating contest. They’re also well known for their bands, with a reputation for booking up-and-coming acts just before their big breakout (think, Neon Dreams), as well as “tickle your fancy” acts like Fred Penner. “Our approach is ‘ridiculousness upon ridiculousness,’” says Beauchesne. “Like, how can we pile it on so it’s just more and more fun?”

Rather than doing food trucks, local restaurants apply for the festival, preparing a special menu. “It’s a foodie festival,” says Beauchesne. “There’s more food than you could ever possibly eat. Like, every year it’s like, ‘Oh, I didn’t get to try that poutine made of spaetzle!’”

Beau’s community will have to wait a little longer to enjoy Oktoberfest; though many cities are celebrating their first year fully back after the pandemic, Beau’s is sitting this year out, though Beauchesne says they’ll be back “bigger and better” in 2023. In the meantime, though, they are continuing with what has been a major pillar of all Oktoberfests: giving back.

“It’s always been conceived of as our signature fundraising event of the year,” Beauchesne says. “What’s neat is that if, say, the local Lions Club gets together 50 people and you come and volunteer at the festival, we pay back that volunteer time as a donation to the organization,” she says. “It’s a win-win, because instead of paying, say, a third-party sanitation company, we can directly make a donation to their organization.” In usual years, there are also individual activations, like a dunk tank or a midway that raises funds for charities like Hidden Harvest.

This year, though there won’t be an in-person event, Beau’s is hosting a two-month long virtual ride, where participants can pledge to cycle any distance and raise funds for United Way in the process.

And if that’s not the spirit of Gemütlichkeit, we don’t know what is.

This piece was originally published in the September 30th Edition of the Great Taste of Ontario Special Report in the Globe and Mail.